FALC Fall 2024 Fundraising Letter

Autumn 2024

Dear FALC Neighbor,

As we approach the end of 2024, we are writing to ask for your support for the Frankfort Area Land Conservancy (FALC) - see photo below. The land conservancy was created from the grounds of the old Frankfort Golf Course in 2008, with the goal of preserving the natural beauty and habitat of the land within the Conservancy and preventing the high-density development that threatened to change the character of this lovely open land that borders our cottages, be they on Golf Lane, CSA, Wildewood or Ness Rd.

We hope that in the past year you and members of your family were able to enjoy walking through the lovely grasslands which are now connected to CSA via a mowed walking path, allowing access without having to risk the traffic on M-22. You may have spotted one of the many forest creatures that reside on the Conservancy or seen a stand of wildflowers that donors helped plant. Your support has made creating and maintaining the Frankfort Area Land Conservancy possible - thank you!

There are a variety of activities necessary to preserve the natural beauty and health of this land. In partnership with Wildlife and Wetland Solutions, we continue to monitor and remove invasive species that threaten our forests and native prairie grasslands with environmentally-responsible sprays and hand-pulling several times each year. In fall of 2025 we are due again to conduct a prescribed burn to manage thatch build-up and restore a healthy plant ecosystem (recommended every 3-5 years, after the second burn). 2025 will also be the year that we perform the every-five-year professional inspection of the “containment area,” the land under which toxic soil from the golf course was buried within a permanently-sealed impermeable membrane. These core responsibilities, along with the removal of fallen or threatening trees as needed, require an annual budget of close to $10,000, our fundraising goal for this year.

We do these things so that all of us can continue to enjoy this lovely corner of northern Michigan, delighting in all that this special place has to offer, and ensuring that we are able to pass on to our children not only the land and happy memories, but an appreciation of the delicate balance of nature that exists there.

To continue this work, we would very much appreciate your tax-deductible financial support.

- The easiest way is to go to our online donation site and give using your preferred debit or credit card, Google or Apple Pay, or an ACH bank draft.

- If you prefer, you may send a check made out to the Frankfort Area Land Conservancy to P.O. Box 2194, Frankfort, MI 49635.

- Or from your phone you can text code "GIVETOFALC" to 44-321 and you will receive a link to our donation site.

Again, thank you for your support,

Sincerely,

The Frankfort Area Land Conservancy Board

David MacWilliams, Chair

Ruth Clements-Gottlieb, Secretary

Brian Potter, Treasurer

Nancy Baglan

David Belknap

Lucas Nerbonne

Beth Madden

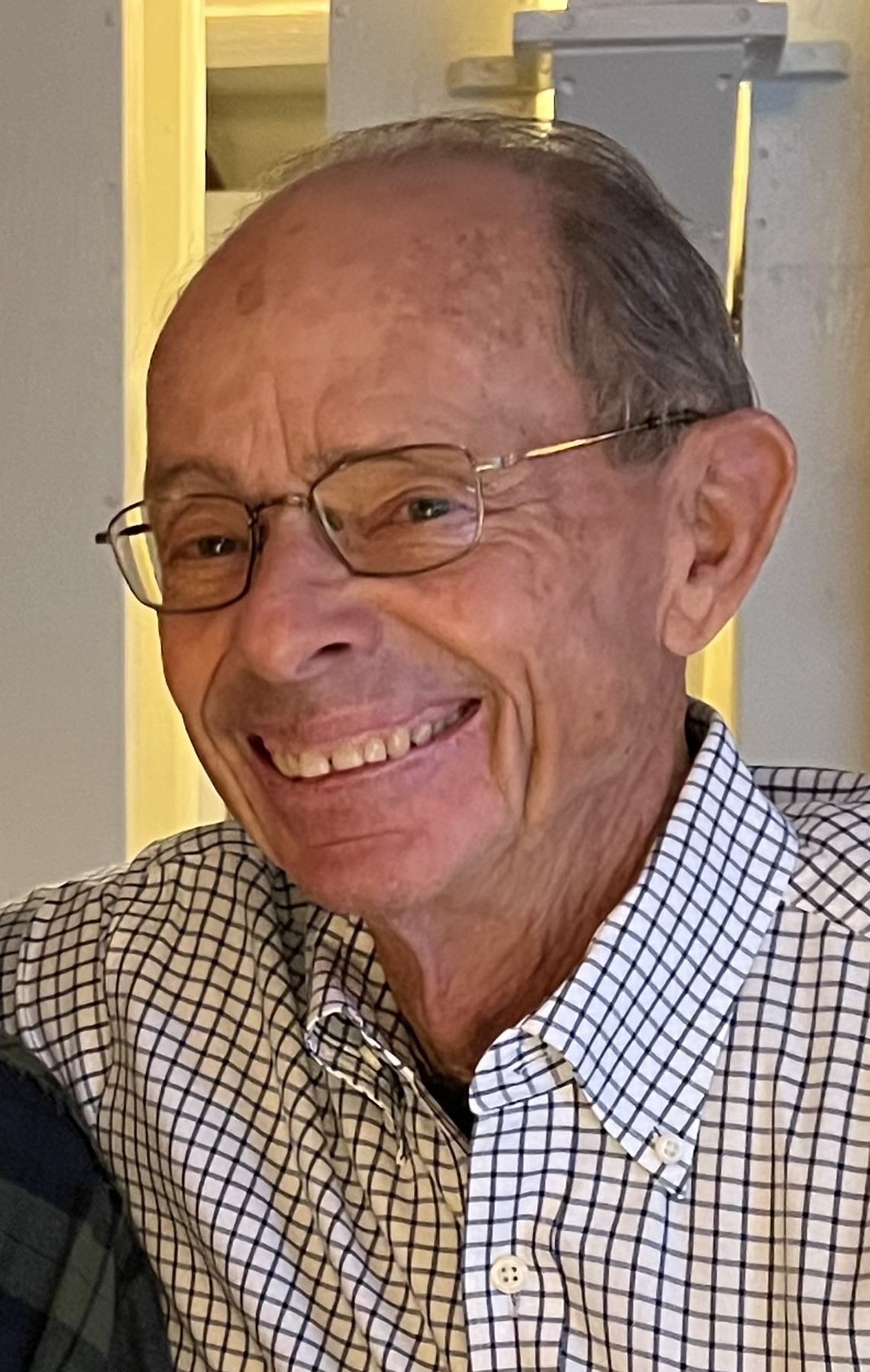

Make no mistake about it, teaching and coaching are a grind. Adults first at 8:30am, then a procession of youngsters leading up to adjournment at noon. Five days a week. Adjusting and modulating your approach, from barking at latecomers to adult lessons, to, in a perhaps more gentle fashion, letting kids know what is expected of them. Nine weeks. The assembled staff responded and made the season a huge hit.

Make no mistake about it, teaching and coaching are a grind. Adults first at 8:30am, then a procession of youngsters leading up to adjournment at noon. Five days a week. Adjusting and modulating your approach, from barking at latecomers to adult lessons, to, in a perhaps more gentle fashion, letting kids know what is expected of them. Nine weeks. The assembled staff responded and made the season a huge hit.